The Great Migration: How the Cost Cap Is Bleeding F1’s Engineering Talent to Tech

- CT

- Dec 14, 2025

- 7 min read

Formula 1 has long marketed itself as the pinnacle of automotive engineering, a meritocracy where the world’s brightest minds compete in a high-speed arms race. For decades, the trade-off for the sport’s grueling hours and relentless travel was a simple economic pact: F1 paid better, offered more prestige, and provided a technical challenge unmatched by any other industry. However, the introduction of the Financial Regulations—specifically the budget cap—has fundamentally broken this pact.

As the 2025 season unfolds under a baseline cost cap of $135 million, a quiet crisis is gripping the paddock. It is not a crisis of horsepower or aerodynamics, but of human capital. Faced with a regulatory ceiling that suppresses wages in a hyper-inflationary global economy, Formula 1 is suffering a structural "Brain Drain." Top-tier engineering talent is increasingly defecting to the technology and finance sectors, where compensation packages are unencumbered by artificial limits, leaving teams to fight a desperate rearguard action to retain the minds that design their cars.

The Inflationary Vise: Austerity in a Boom Economy

The F1 cost cap, introduced in 2021, was designed to level the playing field and prevent financial collapse. For the 2025 season, the baseline sits at $135 million for 21 races, with an additional $1.8 million allowance for every race thereafter (MotorSport Magazine, October 2025). While this mechanism successfully halted the spending wars of the Mercedes-Ferrari dominance era, it failed to account for the post-pandemic economic reality.

The cap covers the vast majority of team personnel, with exemptions only for drivers and the three highest-paid staff members (PlanetF1, June 2023). This creates a "capped majority" whose salaries are pitted directly against the car’s development budget. Every dollar spent on a wage increase for a composite engineer is a dollar removed from the front wing development program. This zero-sum game has forced teams to suppress wages just as global inflation spiked, effectively eroding the real purchasing power of the sport's workforce.

Adrian Newey, the sport’s most celebrated designer, has identified this dynamic as a critical failure of the regulations. In a stark assessment, Newey argued that the cap comes with "hidden penalties," the most damaging of which is that Formula 1 is "no longer the best-paid industry" (PlanetF1, January 2025). He noted that while teams previously lost staff to rivals within the paddock, they are now "losing people to tech companies because they pay better" (PlanetF1, January 2025).

The Salary Chasm: F1 vs. Big Tech

The data supports Newey’s assertion. A forensic comparison of 2024-2025 salary statistics reveals a widening chasm between Formula 1 and the external technology sector, particularly for senior technical roles. The prestige of working for Ferrari or Red Bull is no longer enough to bridge the gap in base compensation.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Engineering Compensation (2025 Estimates)

Role Level | Formula 1 (UK Base Salary) | Tech/Software Sector (UK Base) | Tech/Software Sector (US Base) |

Graduate Engineer | £33,000 - £38,000 (FluidJobs, Dec 2024) | £31,000 - £42,000 (Reed, 2025) | $90,000 - $130,000 (UpGrad, Jan 2025) |

Engineer (3-5 Years) | £45,000 - £65,000 (FluidJobs, Dec 2024) | £50,000 - £80,000 (Ravio, Oct 2025) | $130,000 - $170,000 (UpGrad, Jan 2025) |

Senior Engineer | £63,000 - £96,000 (FluidJobs, Dec 2024) | £80,000 - £110,000+ (Ravio, Oct 2025) | $200,000 - $300,000+ (UpGrad, Jan 2025) |

Principal/Head of Dept | £85,000 - £125,000 (FluidJobs, Dec 2024) | £110,000 - £150,000+ (Ravio, Oct 2025) | $300,000+ (UpGrad, Jan 2025) |

Note: Tech Sector (UK) 'Engineer' and 'Senior' figures derived from median data for mid-level and senior software roles.

As illustrated in Table 1, a Senior Engineer in Formula 1—a role that requires specialized expertise in areas like Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) or composite materials—can expect to earn between £63,000 and £96,000 (FluidJobs, December 2024). While respectable, this is eclipsed by the technology sector. In the UK, the median base salary for a Senior Software Engineer has reached £110,200 (Ravio, October 2025). The disparity is even more violent when compared to the US tech market, where similar roles command upwards of $200,000 to $300,000 (UpGrad, January 2025).

Even within the motorsport sphere, F1 is losing ground. Former Red Bull engineer Blake Hinsey revealed that he was offered a race engineering role in F1 with a maximum salary lower than what he earned working part-time for a World Endurance Championship (WEC) team (GrandPrix.com, February 2025). This highlights how the cost cap has uniquely depressed F1 wages relative to other racing series that do not operate under such strict personnel constraints.

The Recruitment Wars: Loopholes and Signing Bonuses

Faced with this talent exodus, teams are resorting to aggressive and often creative financial engineering to secure staff. The battleground has shifted from pure salary to "signing bonuses" and complex contract structures designed to mitigate the immediate impact on the cost cap.

The Signing Bonus Dilemma

Teams are increasingly using signing bonuses to lure talent, but this practice is fraught with regulatory risk. A signing bonus is generally considered a "Relevant Cost" under the Financial Regulations and must be accounted for. The treatment of these bonuses—specifically whether they can be amortized (spread out) over the life of the contract or must be booked entirely in the year they are paid—is a critical tactical battleground.

Aston Martin’s recruitment strategy, which included luring key personnel like Dan Fallows, came under scrutiny when the team was fined $450,000 by the FIA in 2022 (Formula1.com, October 2022). The FIA’s audit revealed that Aston Martin had incorrectly excluded or adjusted 12 separate costs, specifically including "a signing bonus cost" (Formula1.com, October 2022). This case serves as a warning shot: while teams are desperate to pay talent, the FIA is rigorously policing the accounting mechanisms used to do so.

The "Gardening Leave" Weapon

Recruitment is further complicated by "gardening leave"—the period a departing engineer must sit out before joining a rival to protect intellectual property. In the pre-cap era, teams would happily pay a senior engineer to sit at home for 12 months just to keep them away from a rival.

Under the cost cap, this is a dangerous luxury. Paying a salary to someone who is not contributing to car performance is "dead money." Consequently, teams are becoming more reluctant to place staff on long gardening leave unless they are truly critical. This has paradoxically made the labor market slightly more fluid at the mid-level, as teams release staff earlier to get them off the books. However, for senior figures, the gardening leave periods remain a major barrier, often requiring the poaching team to "buy out" the contract, further complicating the cap accounting.

The Geographic Distortion: Audi’s Swiss Headache

A specific and severe market distortion has emerged regarding Audi’s entry into Formula 1 in 2026. Audi is taking over the Sauber team, which is based in Hinwil, Switzerland. While Switzerland offers a high quality of life, it is also one of the most expensive labor markets in the world.

The $20 Million Disadvantage

Mattia Binotto, leading the Audi project, claimed the team would be at a $20 million disadvantage without regulatory intervention due to Swiss labor costs (BlackBook Motorsport, October 2024). Data shows that the average salary at Sauber is approximately £125,000 ($161,500), compared to an average of £90,000 ($117,200) at the top three UK-based teams (BlackBook Motorsport, October 2024).

This creates a mathematical impossibility under a flat global cap. For every engineer Audi hires in Hinwil, they spend significantly more of their capped budget than Red Bull or Mercedes spend for an equivalent engineer in the UK.

The OECD Offset Solution

To prevent Audi from starting with a 30-40% staffing deficit, the FIA has agreed to a controversial "salary offset" for 2026. This mechanism will use OECD wage data to allow Audi to deduct a portion of their labor costs, effectively normalizing their Swiss salaries to UK levels for the purpose of the cap (Motorsport.com, October 2024). While intended to ensure fairness, rival teams fear this creates a state-sanctioned loophole. If Audi can pay a higher headline number (to match Swiss living costs) that is then discounted by the FIA, they may become the most attractive employer in F1, luring talent away from the UK’s "Motorsport Valley" with salaries that look massive to a British engineer but "normal" to the Swiss accountants.

The Pipeline at Risk: Oxford Brookes and Imperial College

The impact of these economic shifts is being felt most acutely at the university level. Institutions like Oxford Brookes University and Imperial College London have traditionally served as the primary feeder schools for the sport. Oxford Brookes, located in the heart of the UK's "Motorsport Valley," recently opened the "Reynard Wing," a world-class facility designed to maintain its status as a premier training ground (Oxford Brookes, November 2025).

Despite these investments and the university's continued success in competitions like Formula Student (Oxford Brookes, July 2025), the pathway from graduation to the paddock is narrowing. With the finance and tech sectors actively recruiting from these same engineering pools—offering starting salaries that can be nearly double those of F1—the "default" choice of a motorsport career is being challenged.

However, students graduating with heavy debt loads are increasingly pragmatic. When a FinTech firm in London offers £60,000 and a 9-to-5 schedule, and an F1 team offers £35,000 and 24 weekends away from home, the "dream job" loses its luster.

The 2026 Mirage: Why $215 Million Won't Fix It

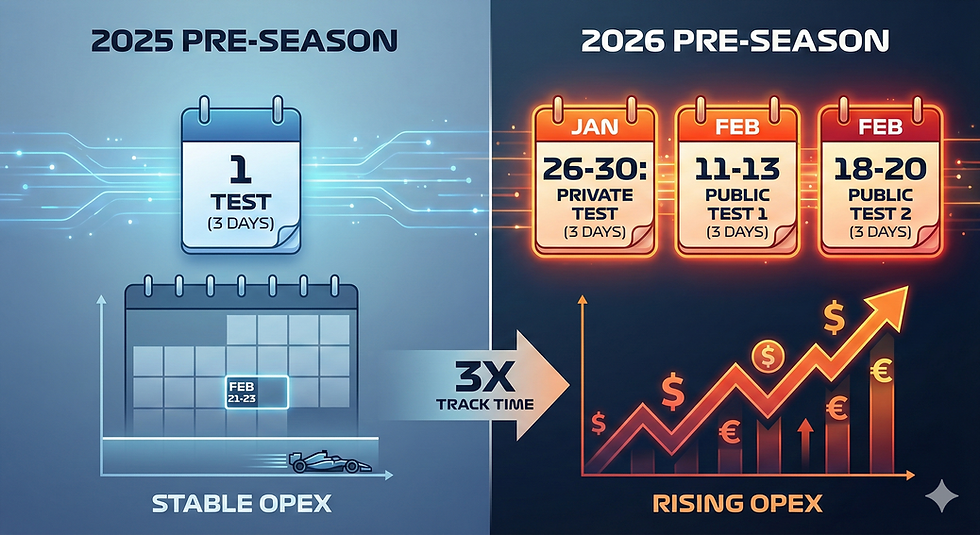

Optimists point to the 2026 regulatory overhaul as a potential release valve. The headline cost cap figure is set to rise significantly to $215 million. However, industry analysts warn that this increase is largely a mirage.

The jump from $135 million to $215 million does not represent a windfall of new spending power. Instead, it reflects the absorption of costs that were previously exempt or classified differently, alongside adjustments for cumulative inflation (Coffee Corner Motorsport, September 2024). The new figure will include "most staff salaries" and other operational expenses that were previously outside the perimeter (Coffee Corner Motorsport, September 2024). Consequently, the pressure to suppress individual wages to maximize development spend will remain unchanged. The "pie" is getting bigger only because more ingredients are being counted, not because the teams are being allowed to eat more.

Conclusion

The Financial Regulations have undeniably achieved their primary goal: preventing the financial ruin of the grid. However, they have created a secondary crisis that threatens the sport's identity. Formula 1 is attempting to operate a deflationary labor market within an inflationary global economy.

As the gap between F1 salaries and tech sector compensation widens—evidenced by the stark disparities in Table 1—the "Brain Drain" is shifting from a trickle to a steady stream. With senior engineers earning significantly less than their peers in software development, and graduates facing the reality of stagnating entry-level pay, the sport relies heavily on prestige to retain its workforce. But as Adrian Newey warned, prestige does not pay the mortgage. Unless the regulations evolve to allow for competitive wage growth—perhaps through broader exemptions for engineering talent or a more dynamic inflation index—Formula 1 risks becoming a training ground for the tech giants, rather than the destination for the world’s best engineers.

Comments